In 1987, the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF), a London-based anti-apartheid solidarity organisation, was looking for a way to help turn US and UK support away from the apartheid government.

While support for the struggle was growing globally, the UK and US were still firm allies of the apartheid regime. South Africa’s muscular foreign policy had been targeting these countries with propaganda about the reasonableness and benefits of apartheid for some decades, but Horst Kleinschmidt (the IDAF director) and Trevor Huddleston (the IDAF chair) hoped that soft-hearted individuals would respond to the considerable plight of South Africa’s children.

South African police and army had been directing their almost unlimited powers at children and young people after 1976, as the student and grassroots movements gathered momentum in the 80s, and during the rolling states of emergency of the mid-80s. Their scope was vast: in townships, Namibia and in the neighbouring “frontline” states.

Children were frequently victims in cross-border incursions and it is displaced children (living in very difficult conditions) who were mostly in Swapo, Zanu and ANC camps. In Namibia, when demoralised by losses against liberation fighters, the South African army would attack schools, blow up buildings and dormitories by gunfire, mortar bombs or petrol bombs. They set up military and police bases close to schools and harassed, raped, assaulted, detained and tortured the pupils. A Unicef study published in April 1989 estimated that 25 children died every hour from the effect of South Africa’s war against the southern Africa frontline states between 1980 and 1988. Many deaths among infants and children —330 000 in Angola and more than 490 000 in Mozambique — were as a direct or indirect consequence of South African aggression or destabilisation (and a further 25 000 infant and child deaths for that same period in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia).

In South Africa, the targeted war on the young caused the arrest between 1984 and 1986 of 18 000 children under the age of 18. Thousands were killed, tortured and assaulted. “Hundreds of reports reached us of apparently random assault, harassment and the shooting of youth in the streets, at school, on the way to shops, at funerals and vigils and so on,” Frank Chikane reported at the Children, Repression and the Law in South Africa Conference. And from these reports a pattern emerged of a deliberate policy of terrorising the youth.

The Detainees’ Parents Support Committee (DPSC) offered three reasons for detaining children. The first to force a confession; the second to obtain information about others; and the third simply “to strike fear and terror into the hearts and minds” of those detained; and inevitably their families too. Families were sometimes taken hostage. In Soweto, police arrived to detain a family’s 18-year-old son. On being told that he was not home, they arrested the entire family including a one-month-old baby and four other children aged five, six, ten and fifteen years.

Without legal representation (or access to parents), many children would spend months in custody without a charge because they were perceived as a threat to society. On 9 February 1986, the City Press newspaper reported the state refused bail for an eight-year-old boy accused of intimidation. Differing studies found between 83 and 93 percent of all detainees were tortured. Only one of the 65 detainees interviewed by the DPSC was not assaulted.

The South African army would recruit teachers (or place white soldiers into schools as teachers) and pupils to spy and issue them with firearms. Vigilantes were armed and even transported by police. They would deploy librarians and social workers to spy, spread propaganda and otherwise dissuade black consciousness and charterist ideologies. In Namibia, they even established church and missionary organisations to attack the churches and church leaders that were on the side of the resistance.

The decision to organise and resist by South African youth was taken in the face of the life of violence they were already exposed to everyday. A member of Tsakane Youth Congress on Johannesburg’s East Rand, Elias Kodisang, remembers his schooling: “I am not even sure how we actually learned. Everything was by rote, and anything you got wrong, you got severely beaten and tortured for it. In my time, about three of my classmates committed suicide.” His teacher broke all ten of his fingers, and to this day, he cannot use his fingers properly. “Like any black child the system is in your face. You live it,” he remembers.

The Children, Repression and the Law in South Africa Conference

Huddleston and Kleinschmidt organised the Children, Repression and the Law in South Africa Conference together with the ANC’s Aziz Pahad and Thabo Mbeki, who decided to hold it in a frontline state so that South Africans could attend. They settled on Harare, and Kleinschmidt went to negotiate the terms with Robert Mugabe, who had been a beneficiary of IDAF when he was a prisoner. A decision was taken to have Huddleston, a man of significant influence in the West, be the face of the event. The secretive nature of IDAF’s work compelled them to direct the conference through the Bishop Ambrose Reeves Trust. Kleinschmidt travelled multiple times to Harare to arrange for an event that would bring together the external (exiles and the solidarity movement) and internal resistors to apartheid (ordinary women and children, churches, trade unions and movements resisting apartheid).

The South African government tried to keep people away, but many were brought into the country without travel papers. Children and young people came at considerable risk to themselves and their families together with South Africans with a duty of care to children including lawyers, doctors, religious and social workers. They were joined by representatives from 45 countries from across the ideological divide. In all more than 700 delegates met and stayed at the Harare Hotel. It quickly ran out of accommodation. To their dismay people, when they slept, did so in the corridors. “For the first time the authentic voice of South African people was heard delivering its own message to the world,” Huddleston reflected. “The conference … enabled the whole international community to break through the veil of censorship and secrecy imposed by the apartheid regime’s two year old state of emergency.”

The apartheid regime’s severe censorship and banning of people, meetings and organisations over all the decades had done its work of estrangement. This was never more evident than in this first encounter for South Africans with Oliver Tambo at the conference. Here was a man who had not been seen in South Africa since 1959. As Victoria Brittain recalls, there was at first a stunned silence and then an outpouring of emotion. But it was not merely the exiled ANC that was reunited with South Africans. It was South Africans of all colours and manner of resistance, “with only the limited experience of a fragment of their own closed society,” meeting each other for the first time. Haunted by the fear of futility, and terrorised by the trauma of violence and the dogged efforts of the government to sow division, the conference offered weary souls “a precious foretaste of a post-apartheid society. Colour, status, power-structure were deliberately and joyfully forgotten.”

“There are no children in South Africa”

ANC stalwart Ruth Mompati quoted a student at the conference as saying, “There are no children in South Africa” – so many had fled, and those that stayed behind had sacrificed their childhood. For those four days, delegates sat witness to testimonies from children whose bodies had been broken by indiscriminate and purposeful violence. Their soft-spoken, halting and fearful accounts were sobering. The spectre of Minister of Law and Order, Adriaan Vlok loomed large in their accounts. They were afraid of what he had waiting for them on their return to South Africa.

On 14 June 14 1986, the South African Defence Force attacked Gaborone, where Nthabiseng lived. “I was visiting my aunt … I went into the bedroom to get something and I heard a bang. I went out and saw a masked man. I turned to run and was shot; I continued to try and run away but another man stood up in front of me and knocked me down. I was shot in the back as I lay on the ground.” Nthabiseng, who had never even been to South Africa, was paralysed from the waist down while her aunt was murdered.

“On the second day I was taken to Kempton Park Police Station. I was given electric shocks. I was stripped and put in a rubber suit from head to foot. A dummy was put in my mouth so I could not scream. There was no air. They switched the plug on. My muscles pumping hard, no signs on my body. I couldn’t see anything. When they switched the plug off they took the dummy out and said I should speak. When I refused, they put the dummy back and switched on again. After a long time, they stopped. I was stripped and put into a refrigerated room naked. I was left there. In the fridge it was also something like 30 minutes. Then they brought me out again and put me back in the electric shock suit.” Buras Nhlabathi, age 17, interrogated and tortured for three months.

William was eleven years old when he was detained by the South African police in October 1986. He was kept for two months and two days in a mortuary, a dark room and a cell around Krugersdorp. His brief testimony was barely audible, his head hanging heavy on his chest. “They (the police) said I burned cars and shops.” The police knocked all his teeth out during his detention. It was clear he was still in shock. While he was at the conference, his two brothers and sister were still in detention. “His presence on the platform said enough,” recalled Huddleston.

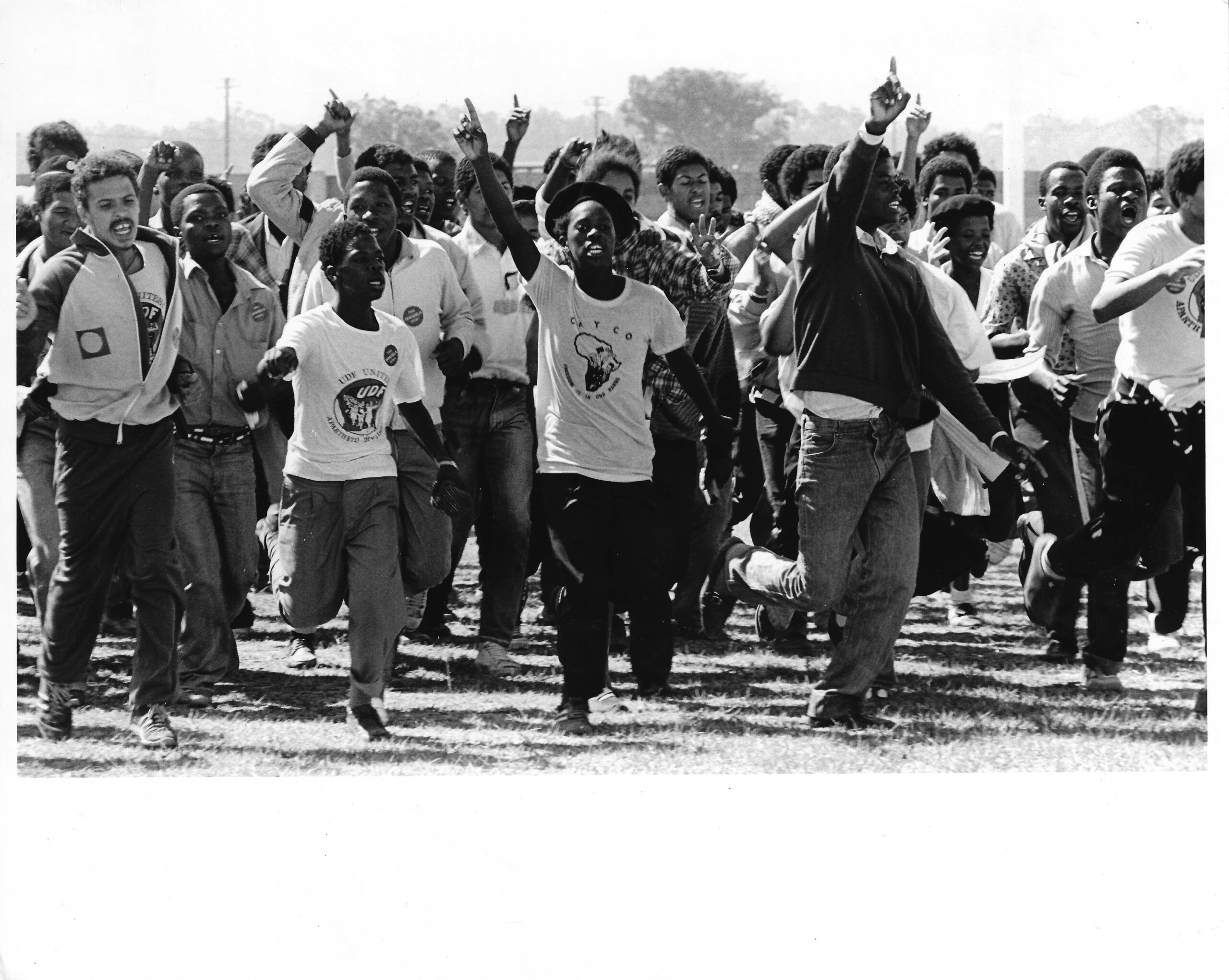

To the children the statements and testimonies offered the opportunity to proclaim not so much their innocence or victimhood, but their guilt. They proudly owned up to their organised resistance. But the refusal to submit to the fear of state violence came at the price of unprecedented brutality. The United Nations recognised this, saying, apartheid, in particular its treatment of children, was “a series of acts of genocide”.

They shook the world

Abdul Minty remembers how moving the children’s resilience, their power to organise and their defiance was. But at the conference and thereafter it was the assault, detention and torture that “shook the world.” What was needed were the stories to strike soft hearts after all. To this end the conference was successful. It was timely too (perhaps conveniently so). The conference took place shortly before a meeting in October of that year of Commonwealth heads of state in Vancouver, Canada, to discuss sanctions. It also preceded a US State Department report to Congress on the question of South Africa’s response to sanctions imposed the year before. Huddleston viewed it as a milestone in the liberation struggle: “The Harare Conference stimulated a movement across the world to mobilise action to defend and protect the children who are victims of apartheid”.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement published the conference’s proceedings extensively. South Africa was humiliated on an international stage. Resolutions and statements condemning the treatment of children were taken by the Commonwealth heads of government, the European Economic Community, the British House of Commons, the United States Senate and the UN General Assembly.

Minister Vlok complained that the conference had caused South Africa untold damage. He released a few detainees and countered the claims with a staged soccer event between detainees. Fewer children and youth were detained in the time that followed, but the government did not stop. Sicelo Dlomo, whose account of detention was featured in a television documentary in the US, was identified by police, questioned and released. Five days later, his body was found, a single bullet to the head.

This article was developed as part of the blog project “Troubling Power: Stories and ideas for a more just and open southern Africa”, which marks the 40th anniversary of the Canon Collins Educational and Legal Assistance Trust.

Elias Kodisang, who cooperated in the writing of this piece, is a Canon Collins Scholar